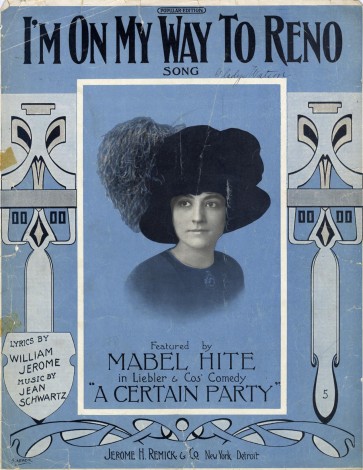

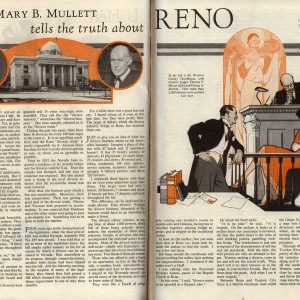

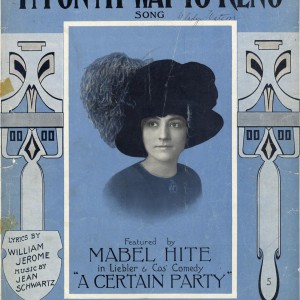

It didn’t take long for Reno to enter the popular culture of its day, not only as a place to divorce, but also for its colorful mystique. Munsey’s Magazine dubbed Reno “the nation’s new divorce headquarters” in 1909, and in 1910, a popular song “I’m on my way to Reno” hit the music charts. Soon, the country was singing along with the jaunty chorus:

I’m on my way to Reno, to break the Marriage Knot,

You just get off the train and drop a nickel in the slot,

You just get off the train and then,

Turn round and then jump on again,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom.

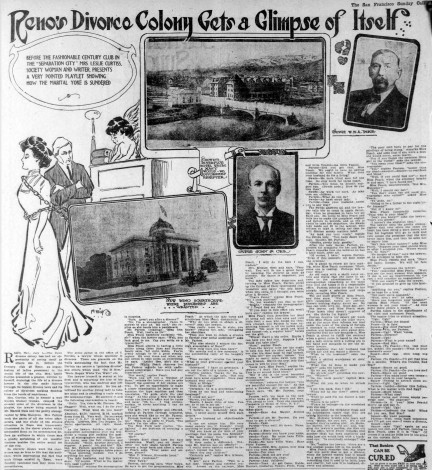

Some playwrights found inspiration by witnessing the scene firsthand. Leslie Curtis, an actress and reporter (but emphatically not a divorce-seeker), arrived in Reno in October 1909. At first intending only to report on the colony, she proceeded to pen a number of “playlets” about Reno’s unique environment. The first, titled Housekeeping in Reno, was performed for the local Twentieth Century Club in 1909. The second, The Reno Divorce Mill, took the stage of Reno’s Majestic Theater the following May. Its slapstick plot starred a Reno lawyer trying to woo his stenographer (“Ima Peach”) while enduring a series of interruptions from a steady stream of demanding divorce-seekers.

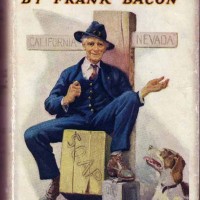

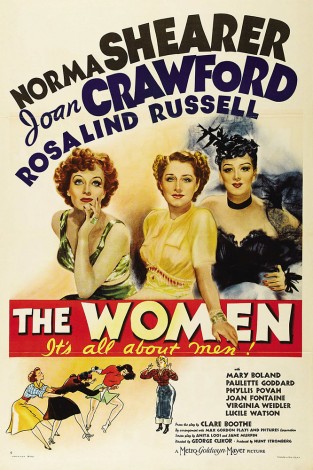

The Nevada divorce graced stages further afield, as well. The play Lightnin’, set not in Reno but in a fictional hotel straddling the Nevada-California border, opened in New York City in 1918, and became one of the longest-running plays in Broadway history. And in 1936, Clare Boothe Luce penned the play, The Women, based loosely on her own 1929 Reno divorce from George Tuttle Brokaw.

Reno took center stage in Woody Guthrie’s 1937 song, “The Philadelphia Lawyer” (originally “The Reno Blues”), which featured a love triangle between the eponymous lawyer, a Hollywood maid, and her gun-toting cowboy husband, Bill. The song was later recorded by a number of artists including Rose Maddox & the Maddox Brothers, Bonnie Owens, and Tennessee Ernie Ford.

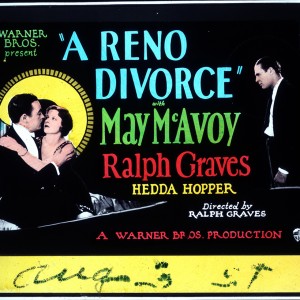

Hollywood musicals often featured some of the most entertaining references to Reno’s divorce colony. These included the elaborate dance number, “Alimony Hotel,” performed by a large cast of dancing divorcées led by Lillian Roth in a 1934 short.

Featured Resources

The Women

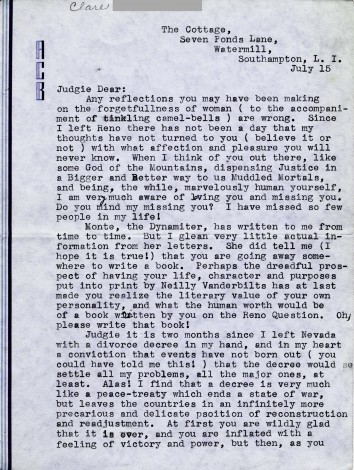

Clare Boothe Brokaw was in her mid-twenties when she traveled to Reno for three months in 1929 to divorce her first husband, millionaire George Tuttle Brokaw. She stayed at the Riverside Hotel and hired as her lawyer Judge George Bartlett, known affectionately to his many clients and colleagues as Judgie.

After her divorce, Clare Boothe returned to New York and worked as an editor for Vanity Fair magazine before marrying Henry R. “Harry” Luce, the editor-in-chief of Time, Inc. In 1934, she left her magazine job to pursue a career as a playwright.

Her play, The Women, based loosely on her own experiences, was an immediate hit when it opened on Broadway on December 26, 1936. The plot focused mainly on the interactions of a group of wealthy New York women undergoing varying degrees of marital strife. While little of the play was actually set in Reno, Reno’s image was so embedded in the American psyche that no specific staging was necessary for there to be universal understanding of the play’s themes.

In 1939, the film version of The Women was released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. In the film, the Reno action was moved from the Riverside Hotel to an anonymous stage-set dude ranch reportedly inspired by the Washoe Pines Guest Ranch.

Luce became an accomplished writer and also served as a U.S. Ambassador, first to Italy and then Brazil. Drafts of her unpublished manuscript of an earlier novel version of The Women can be found in the Clare Boothe Luce Collection at the Library of Congress.