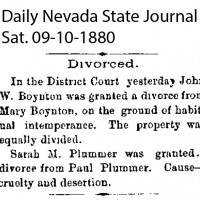

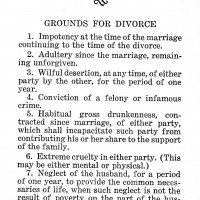

Regarding the question of fault, Nevada borrowed from Utah’s divorce law, but eliminated its no-fault clause. Nevada divorces followed the principle of fault, granting the divorce to the party with the least amount of fault. As a result, one spouse (the plaintiff) had to charge the other (the defendant) with one of the actions or behaviors legally recognized as sufficient justification for divorce. When none of the legal options seemed strictly applicable (when, for instance, a person simply wanted to marry someone else), divorce-seekers still had to offer plausible testimony in support of one of these grounds.

- Impotency at the time of the marriage, continuing to the time of divorce

- Adultery since the marriage, remaining unforgiven

- Willful desertion by either party by the other, for the space of two years

- Conviction of a felony or infamous crime

- Habitual, gross drunkenness, contracted since marriage, of either party, which shall incapacitate such party from contributing his, or her share, to the support of the family

- Extreme cruelty in either party (physical or mental)

- Neglect of the husband for the period of two years, to provide the common necessities of life when such neglect is not the result of poverty on the part of the husband, which he could avoid by ordinary industry

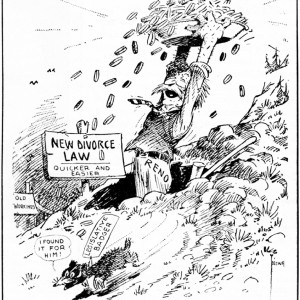

The Nevada legislature revised the divorce law in 1931, lowering the period of time for desertion and neglect to one year and adding two grounds for divorce:

- Insanity existing for two years prior to commencement of the action

- When the husband and wife have lived separate and apart for three consecutive years without cohabitation the court may, in its discretion, grant an absolute decree of divorce at the suit of either party

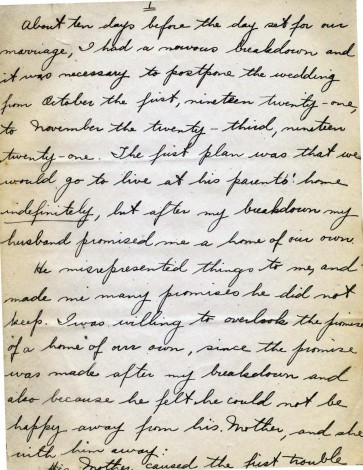

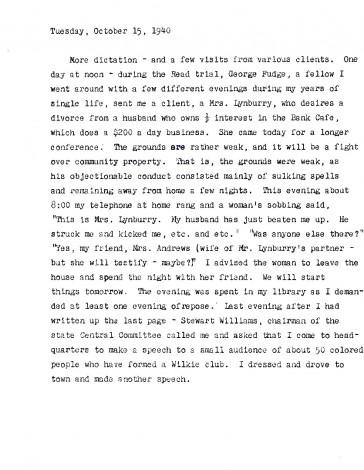

Extreme cruelty was typically presented to be of a mental nature. Acceptable evidence of cruelty would show that the defendant had been unkind, indifferent, found fault, quarreled, stayed out nights, was neglectful, and other conduct that caused the plaintiff unhappiness and affected his/her happiness to such an extent as to make life together no longer possible.

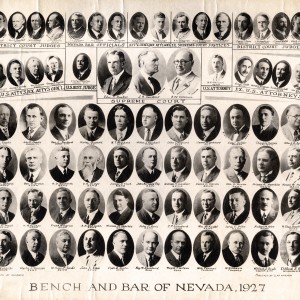

Insanity was the one ground for which the court required a significant amount of corroborating evidence. The defendant would be assigned a Guardian Ad Litem—in this case, a Reno lawyer who would protect the rights of the defendant, who was a ward of the state in which he or she lived and was institutionalized.

Whereas little in the way of evidence was required for the other grounds, insanity required testimony from mental health professionals, usually a doctor familiar with the specific case, and/or the administrator of the mental hospital, as well as depositions from family members attesting to the defendant’s insanity and the fact that the condition was incurable.

Regarding the question of fault, Nevada borrowed from Utah’s divorce law, but eliminated its no-fault clause. Nevada divorces followed the principle of fault, granting the divorce to the party with the least amount of fault.

Spend a few days in a Reno divorce court and you will have enough novel definitions of 'extreme cruelty' to fill a page in the dictionary.

Featured Resources

Extreme Cruelty

Like most other states, Nevada did not recognize “irreconcilable differences” as a grounds for divorce in the early 20th century. In the absence of a true no-fault option, the permitted grounds of “extreme cruelty” often substituted for it, with all parties aware that, in many cases, the claim was a bit of a subterfuge.

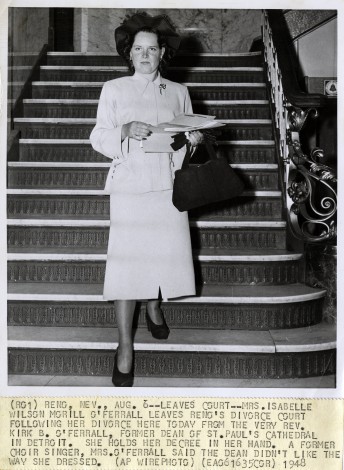

Extreme cruelty was the easiest ground to prove, and ultimately seemed the least damaging to the defendant, given the more serious nature of the alternatives. According to Reno attorney Clel Georgetta, 90 percent or even more of Reno divorces cited cruelty as the motivation.

The 1961 film The Misfits, opens in Reno as Marilyn Monroe’s character, Roslyn, rehearses the testimony she will soon deliver in her divorce proceedings. Thelma Ritter, playing Roslyn’s boardinghouse manager and resident witness, Isabelle Steers, takes the place of the judge who will soon be questioning her in court. In her protest at having to lie about her husband’s behavior, Roslyn reveals her discomfort with expressing words she knows to be untrue.

Isabelle: Did your husband act toward you with cruelty?

Roslyn: Yes.

Isabelle: In what way did this cruelty manifest itself?

Roslyn: He persistently -- how does that go again?

Isabelle: He persistently and cruelly ignored my personal wishes and my rights and resorted on several occasions to physical violence against me.

Roslyn: He persistently-- oh, do I have to say that? Why can't I just say, “He wasn't there?”-- I mean, you could touch him, but he wasn't there.

Other divorce-seekers recounted tales of spouses who refused to allow them to listen the radio in the house, or continually shouted at them. It is, however, important to keep in mind that the cruelty cited in many divorce cases was both extreme and substantiated.