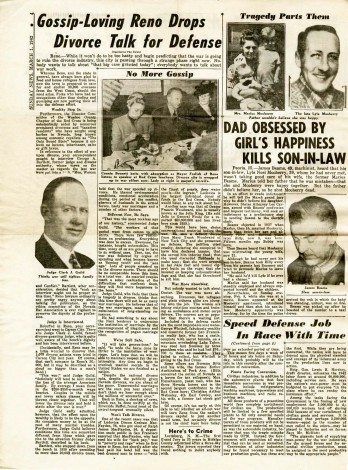

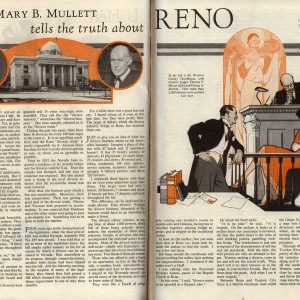

Journalism was the earliest and most constant purveyor of Reno divorce stories. Coverage ranged from factual reports about changes in the law and accounts of prominent divorces to exposés and serialized accounts of the colorful goings on in Reno. Carried by newspapers, national magazines, and tabloids alike, these tasty tidbits were devoured by an insatiable public.

The media attention was nationwide from the start. Laura Corey’s 1906 divorce made the front page of the New York Times, as did those of other prominent society figures taking advantage of “the Reno cure.” By 1910, popular magazines of every genre were sending reporters to Reno to explore the little town’s burgeoning separation center firsthand.

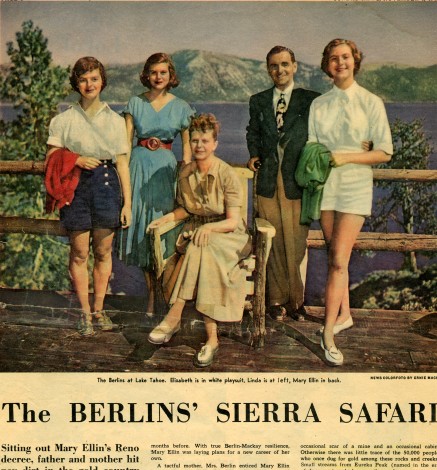

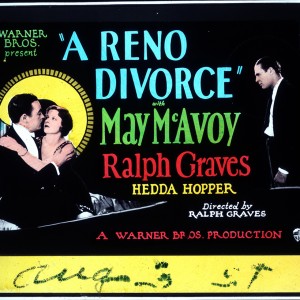

Interest in the Reno divorce intensified in tandem with the rise of celebrity journalism, spearheaded by gossip columnists like Walter Winchell and Hedda Hopper (who actually played a divorce-seeking socialite in the 1927 silent film, A Reno Divorce). Straddling the line between news and entertainment, coverage of Reno’s divorce landscape undoubtedly contributed to the increasing overlap of the two genres.

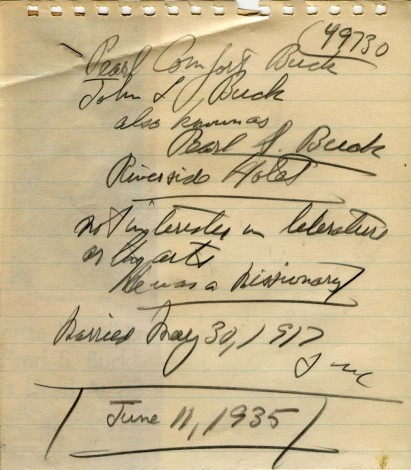

From the 1930s onward, a handful of reporters worked the “divorce beat” in Reno, transmitting colorful stories direct from the divorce colony to media outlets across the country. The most accomplished of these, including Bill Berry of the New York Daily News and Edward A. Olsen of the Associated Press, earned national reputations for their uncanny ability to track down even the most elusive divorce-seekers, from Frank Sinatra to Gloria Vanderbilt. Reporter James Hulse, who later became a Professor of History at the University of Nevada, Reno, worked as a divorce stringer for several Eastern newspapers in the 1950s and early 1960s, earning beer money from the small fees paid for each story filed.

Featured Resources

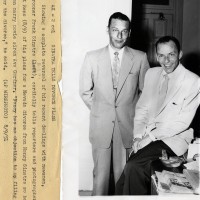

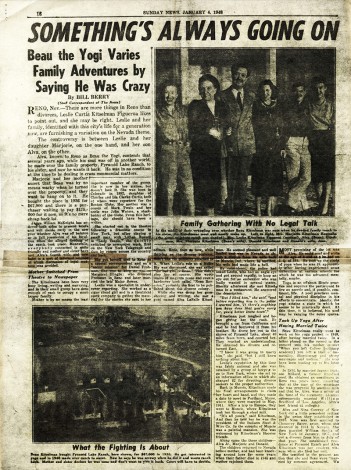

Bill Berry

Reporter Bill Berry worked as a stringer for the New York Daily News from the 1930s through 1950s. Known as much for his tenaciousness as for his effervescent personality, he was one of the luminaries of Reno’s divorce beat.

As one of his competitors, Edward Olsen of the Associated Press, described Berry’s job, “The New York Daily News kept Bill up here to cover nothing but divorces and sex. He didn’t have to worry about airplane crashes or legislatures or governors or anything. He was strictly a divorce and marriage man.”

To get his story, Berry was notorious for tapping into an unsurpassed network of local informants, ranging from guest ranch employees to lawyers to grocery clerks. Some of his most celebrated scoops included locating a 21-year-old Gloria Vanderbilt, in Reno in 1945 to divorce husband Pasquale DiCicco in order to marry conductor Leopold Stokowski. Berry is also credited with being the first to learn of playwright Arthur Miller’s plans to marry Marilyn Monroe after his 1956 Reno divorce.

Above all, Berry was celebrated for his friendliness and good humor. “I never made enemies,” he once said. A friend to Frank Sinatra, whose trials and tribulation he covered closely, Berry was also widely respected for his coverage of winter sports, particularly skiing. He was a strong advocate for preserving the history of skiing, and wrote the book Lost Sierra: Gold, Ghosts and Skis. Bill Berry died in Reno in 1999.