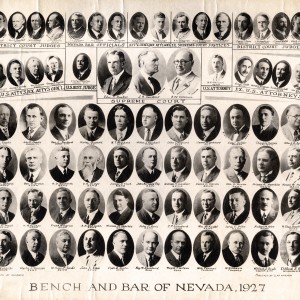

The Full Faith and Credit clause of the U. S. Constitution requires states to respect the laws of other states; however, some Reno divorces encountered challenges in other states on a variety of legal grounds. Most often the objections were over two issues: default divorces, in which the defendant was not represented in court; and the legal definitions of citizenship and residency.

A default divorce occurred when a defendant did not respond to a summons, or could not be located by the person filing a divorce suit against him or her. Instead, a notice would be published in a newspaper where the defendant was last known to have lived–and that would be the only notice that he or she was being sued for divorce. If the defendant did not respond, the Nevada court could issue a default decree. These decrees were found objectionable in some states because, in these cases, the defendant did not appear in a Nevada court and therefore did not receive representation, a right guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution.

Other challenges were lodged over the legal definitions of residency and citizenship. The concept of matrimonial domicile was often the basis of a challenge. Under standard laws of matrimonial domicile, a woman’s legal residence was that of her husband. This meant that any residence a woman might establish on her own (in Reno, for example) was not her legal domicile. How then could Nevada grant citizenship and the right to file lawsuits to a person whose stated domicile was by definition not a legal one?

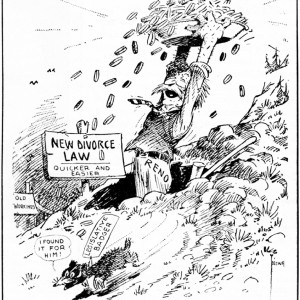

Legal problems occasionally resulted from making public mockery of the state’s liberal residency requirements—the key to the migratory divorce trade. Although every aspiring divorce-seeker stated his or her intention to remain a permanent resident of Nevada, everyone knew that most of these individuals planned to leave the state immediately upon securing a divorce. However, now and then, a divorce seeker would be so vocal about his or her plans to leave Nevada for good that a judge would have no choice but to deny the decree.

Featured Resources

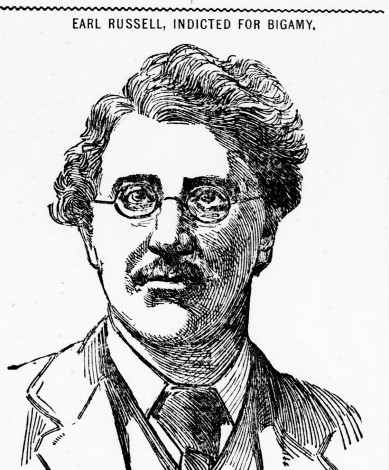

Earl Russell

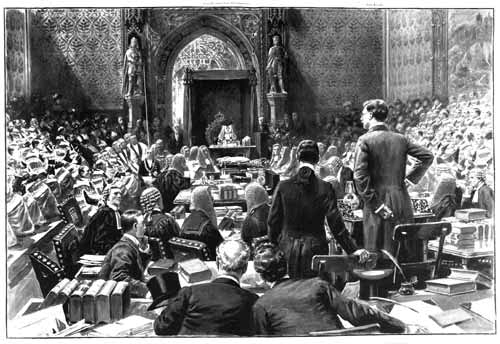

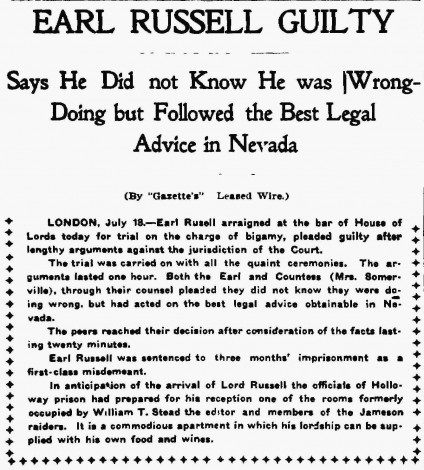

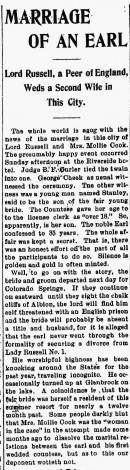

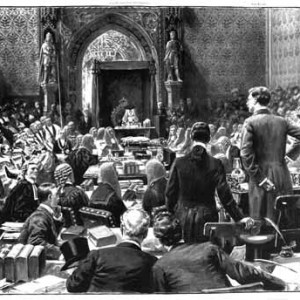

Remarriage after a Nevada divorce occasionally created a situation in which a person would not be able to return home without being charged with bigamy. The 1900 divorce in Genoa, Nevada, of England’s Second Earl Russell, and his subsequent marriage to Mollie Sommerfield at the Riverside Hotel in Reno, landed him in prison upon his return home. England did not recognize Nevada’s divorce laws and charged Earl Russell with the crime of bigamy. Tried by his peers in the House of Lords, Earl Russell professed his belief that his marriage was legal. He pled guilty, however, and was sentenced to three months.

Although later pardoned, Earl Russell fought to reform England’s divorce laws until his death in 1931, but it was an additional six years until the passage of legislation that would have recognized his divorce. There were still certain considerations that British citizens needed to make before obtaining a foreign divorce in Reno.