During the divorce period, Reno had a small minority population that was generally restricted to the east side of town, and it wasn’t until 1959 that Nevada repealed its antimiscegenation laws. Blacks in particular faced de facto segregation in white establishments and neighborhoods. As a result, African-American divorce-seekers were limited in the places where they could live, eat, and recreate. However, from the few accounts of their experiences, we learn how they managed to reach their goals of marital freedom in a parallel divorce universe.

The oldest surviving black congregation in Nevada, Bethel AME, built its first house of worship at 226 Bell Street in 1910. Bethel AME billed itself as the “Biggest Little Church in the West,” and it embraced black divorce-seekers who came for guidance or to share a two-dollar meal at the weekly church social. A boardinghouse associated with the church was located on the site, catering to black congregants and divorce-seekers.

Often black divorce-seekers would come to town with the name of a lawyer and boardinghouse owner in hand, but when they did not, Bethel AME would help them find accommodations. Several of the church elders operated boardinghouses for divorce-seekers, such as the Needhams, whose boardinghouse was located at 501 Elko Avenue. The church also provided entertainment and meals.

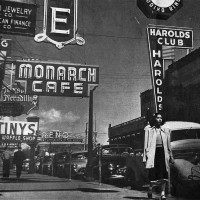

The few other places that offered entertainment to blacks were the New China Club on Commercial Way, which catered to blacks, Asians, and other minority groups, the Elite Club, and Club Harlem in Douglas Alley. These facilities offered casino gaming, but for many years, only Club Harlem, Woolworth’s, a small Chinese restaurant, and the regular AME church socials would serve meals to blacks.

In the 1950s, when showroom entertainment drew crowds to the Riverside and the Mapes Hotel, even well-known, popular black performers could not find a place to stay in the segregated hotels and motels. The first place to cater to African American customers was the Siesta Motel, built in 1946 on West Fourth Street, which served African American automobile tourists and black performers.

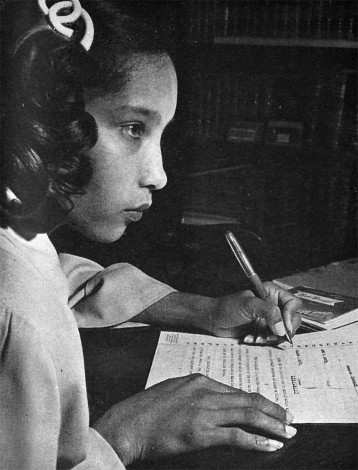

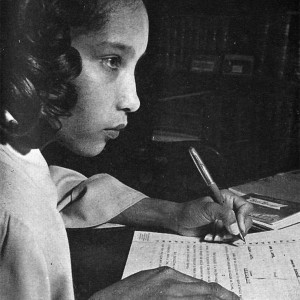

Emma Allen, just 23 years old, arrived in Reno from Richmond, California in 1950 to “take the cure,” as scores of men and women had done before her. The difference between Emma’s Reno experience and those depicted in the mainstream press and popular culture was that Emma was African American.

An Ebony magazine article covering Emma’s six-week divorce from start to finish offers insight into not just the African American divorce experience, but also the nature of Reno’s then-segregated society.

Featured Resources

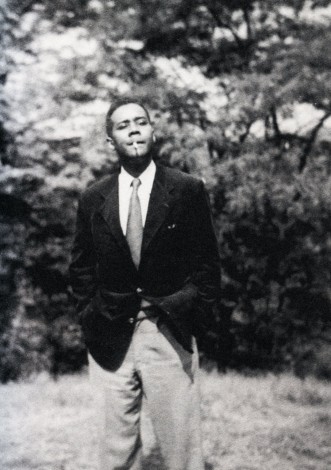

CLR James

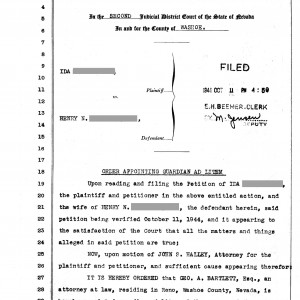

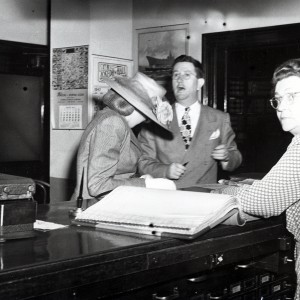

Cyril Lionel Robert (C.L.R.) James was a prominent Marxist writer and intellectual from Trinidad who came to Reno for a divorce in 1948. A previous Mexican mail-order divorce from his first wife had been found unlawful, rendering bigamous his new marriage to white actress and socialite Constance Webb. A trip to Reno was the obvious solution.

Directed to a black-owned boardinghouse on Sierra Street by a white taxi driver, James ultimately found work as a ranch hand at the Pyramid Lake Guest Ranch, and later was allowed by owner Harry Drackert to lodge there. Finding no black attorneys in the entire city, James hired Charlotte Hunter, a liberal and open-minded attorney known to be “strong on the Negro question.”

In between trips to Reno to dine at the “Negro restaurant,” visit the library, and play drugstore slot machines, James worked on an English translation of History of the French Revolution by French historian Daniel Guérin, read French literature, and wrote letters to his wife. The correspondence has been published in the collection, Special Delivery: the Letters of C.L.R. James to Constance Webb, 1939-1948.