Insanity was added as a grounds for divorce by the Nevada legislature in 1931. Nevada courts required a higher level of substantiation for insanity cases than for other grounds, including evidence that the defendant had been hospitalized in a mental institution for at least two years with no hope of recovery. The divorce documents provide us with a rare glimpse into the American mental health field in the first part of the twentieth century and a class of citizens who had lost their freedom.

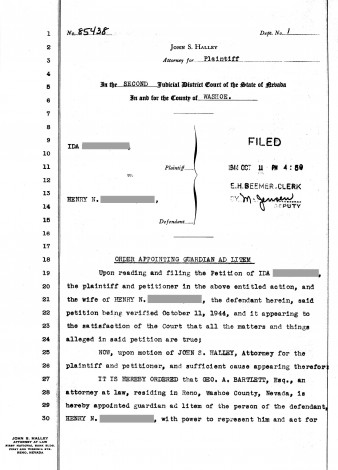

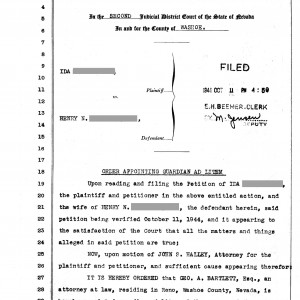

Insanity was the one grounds for which the court required a significant amount of corroborating evidence. The defendant would be assigned a Guardian Ad Litem, in this case, a Reno lawyer who would protect the rights of the defendant, who was a ward of the state in which he or she lived and was institutionalized. Whereas little in the way of evidence was required for the other grounds, insanity required testimony from mental health professionals, usually a doctor familiar with the specific case, and/or the administrator of the mental hospital, as well as depositions from family members attesting to the defendant’s insanity and the fact that the condition was incurable.

The Osborne case

The use of the insanity ground for divorce allowable under Nevada law, while an important outlet for people with a spouse who had been diagnosed with incurable mental illness, revealed the cruelty of American psychiatric practice in the first half of the twentieth century. One especially poignant divorce case illustrates this shockingly common tragedy and how a Reno divorce lawyer restored his client’s freedom and dignity.

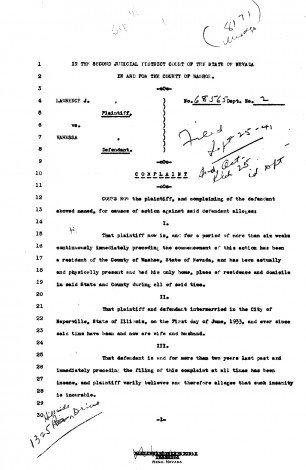

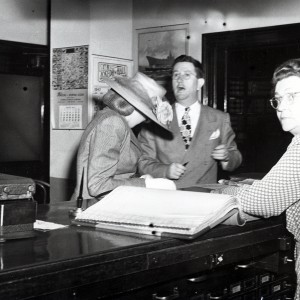

The case began in 1941 as Lawrence Osborne traveled with his children from Wisconsin to Reno to file a divorce suit against his wife, Vanessa. In his initial complaint, Lawrence asserted not only that Vanessa had been insane for at least two years but that in his opinion, her condition was incurable. He also requested full custody of the couple’s two children—Lawrence, 7, and Richard, 4.

It was soon revealed that Lawrence had had Vanessa institutionalized at King’s Park, a psychiatric hospital on Long Island, after a physical breakdown following the birth of her second son. He had then prevented his wife from seeing her children for more than three years.

Convinced of Vanessa’s absolute sanity by letters from her and many of her friends, Reno judge George Bartlett suggested that she file a cross complaint, charging Lawrence with extreme cruelty, which she did. The decree was granted to Vanessa in February of 1942, presumably awarding her custody of the children. Lawrence remained in Reno for a time, becoming Associate Pastor and Minister of Music at the First Methodist Church and remarrying several months later.

The Osborne case demonstrates how frighteningly easy it was to have someone committed before a landmark Supreme Court ruling in 1975. Clearly, Judge George Bartlett played a major role in restoring his client’s freedom.